材料:24in x 48in亚克力白色半透明板/透明板,及14in x14in透空;

14in x14in亚克力白色半透明板/透明板;

18in x18in亚克力白色半透明板/透明板,及4in边框。

地点:纽约上州,Mt. Catskill 南麓。

引子:

这个实验,是和摄影艺术家张海合作,我在林子里设计安装,他进行周期一年的拍摄记录。

树林在一块西向山坡上。土很薄,树长不大,雨后的冲沟下露出七七八八的石头来。

夏天灌木丛生,还有成片的蕨。混着一米多高的野生榉树苗,既挡了可以行走的地方,也遮住了视线。四处横溢流淌的绿色,只是看着已经让人不安。蚊虫嘤嘤嗡嗡,忙忙碌碌,到处是生机;秋天开始,灌木和蕨逐渐败掉,露出苔藓地衣,在透过树枝的阳光下斑斑驳驳,有的贴在半露的石头上,有的裹住坏死的树根。蔓延到树皮上干死后的,开始伴着黑色霉点,混着不同的病菌,变成诡异的图案。

大雪覆盖后的林子,像是因白色吞噬了所有的声音,极度安静。侧耳倾听,什么都没有。雪地里行走的沙沙声,让它更加安静。风暴后倒掉的树,以及不知是枯死还是断掉的树枝,把雪地拱得东倒西歪。年幼的山毛榉往往挂着没掉干净的叶子,在纤细的枝条上摇弋。半透明的黄叶透出细细的经脉,被大雪衬着,淡淡的铅黄成为灰色树林中唯一的颜色。用力搬开冻住的石头,下面是整整齐齐的冰茬儿,冻着硬的泥土,晶莹透明。

4、5月份,几场雨把积雪冲尽以后,昏睡了一冬的虫蛇开始蠕动。头顶的这边或那里,传出啄木鸟当当当的声音。周而复始,开始下一轮的生命。

白尾鹿常常在树林里轻松的穿行。秋天,林子边上的一棵野苹果树下,常常见到一颗颗的鹿粪。有时一头大鹿带着小鹿,有时几只小鹿独行。见到人,它们不急逃走,先呆望一阵,然后转身,几个轻轻的跳跃,瞬间消失在林中。据说这鹿经常繁殖过剩,就有人引来土狼(Coyote)做为天敌。其实每到狩猎季,就会听到山中传来枪响。引来土狼似乎多此一举。

这个实验的起因,是在想早期园林中讲的“如画的风景”(picturesque)。在一个北美地区普通的树林里,我经历了怎样的风景。摄影师的镜头下,什么是如画的风景。

下文是来自2019年秋季上课期间的写作。记录了“如画的风景”(picturesque)的词源学研究,以及安装过程的感受。

Experimental Landscape I

—— “Picturesque”

All hid in snow, in bright confusion lie,

And with one dazzling waste fatigue the eye

—— Ambrose Philips

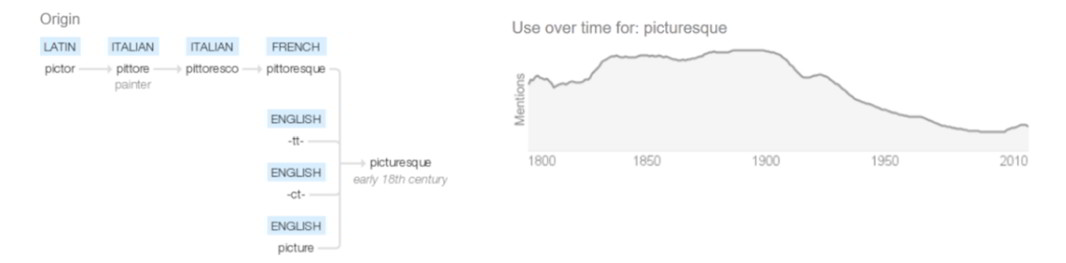

The lexicon of picturesque, “visually attractive, especially in a quaint or pretty style” is pretty much the central meaning. In Merriam Webster, there is a second explanation: “evoking mental images,” which means telling about something in a way that makes it very easy to imagine.[1] The Chinese definition如画的(as a picture) concentrates the appeal and charm of images. And Google define traces the word’s origin and development in the past:

My interpretation of “Picturesque” became the “framed beauty” on October 18th 2019 in a Theory class, as the first time. After reading Oliver Sacks’s The River of Consciousness, I would add an objective definition: “discrete intervals by visual perception.”[2] The scientific meaning indicates how an eye blink interrupts the images as a camera, many thousands of times faster but the same as the discontinuous.

Most people would agree with J.B.Jackson, when he points out that a “picturesque landscape” started with landscape paintings by artists, who discovered beautiful views and composed “pictures of views.”[3] The criteria and judgment of the composition was based on what people could “see,” and what they were trained for: beauty. From the historical derivative of the “picturesque,” John Dixon Hunt pointed that garden design were studied as painted representation of landscape in 19th century with English gardens. Landscape painting could “teach gardenists, techniques of organizing real, three-dimensional space by translating from illusionary painted surfaces.”[4]

Richard Serra, famous for his corten steel sculptures within landscape, tried to demolish “the pictorial qualities” in his works.[5] In Yve-Aliain Bois’s article “A Picturesque Stroll around Clara-Clara,” the early definition of picturesque, the sphere of painting, was reinterpreted with no narrative, no sequence, no experience, but only as Serra’s sculpture “Clara-Clara.” Based on spatial continuities, the changing movement within the sculpture is an experience of reciprocity and mutuality. The sculpture is “as a thesis of smoothness, gentle curves, and delicacy of nature, and as an antithesis of terror, solitude, and vastness of nature.” Price and Gilpin go on to “provide a synthesis with their formulation of the ‘picturesque,’ which is on close examination related to chance and change in the material order of nature.”[6]

Now I start to feel ambiguous about the academic definitions. When and what would people view a landscape as “picturesque?” How do we recognize “picturesque?” Why? Is “picturesque” meaningful in landscape? Furthermore, are we creating “picturesque” in landscape? And should we?

I installed a series of clear and translucent panels in a 14-acre woodland in Catskill Mountain region, which is approximately 100 miles northwest from New York City and 1,000 feet elevation in average. The panels are two clear/frost rectangular frames, 24in x 48in, with a cut out 14in x14in. And another two 18in x18in clear/frost squares with a 14in x 14in cut out in center.

May 26, 2019.

The first time coming to the woods, I hesitated. It was late afternoon. It was rainy. The scenery in front was exotic: A meandering path decoyed me at the edge of the woods, and disappeared deep inside. The mystery of unreachable darkness diffused with uncomfortable wetness.

“Is there anything dangerous?” I asked Hai, my friend who lived in a cabin next to the woods.

“There could be snakes or bears.”he said, “Usually around April and November, before or after hibernation.”

I’m not scared of snakes or bears. I’m afraid of the unfamiliar.

The near horizon was covered with massive understory vegetation: beech saplings, twining ivies, unnamed shrubs, spiked bushes. Bugs and wasps were circling around me with curiosity, then buzzed away. The tree barks were covered with dried green mosses; a creepy patterned disease occasionally carried queerly-shaped holes that I wonder who or what made them: the broken edges were not sharp enough for beavers, and the spot near the roots was too low for woodpeckers. An amount of stones were exposed by the runoff along the slope that decayed the top soil, then nourished the lives underneath: squirmy worms, four-legged lizard-looking reptiles... too repellent to be scrutinized for more details.

I didn’t go far. The endless tall ferns blocked the way, sometimes even my eyesight.

I entered the woods a second time on October 12. The fall color had been dispersed through the whole mountain. Ferns were dying. Mosses were unveiled: some wrapped around the dead branches, some made patterns on exposed roots. Stepping on the leaves, twigs and deer poop, I felt the transparency was encouraged by the sparser foliage. Beauties were exposed.

Here was the glade. The trees circled around it had died, their bodies buried by ferns and grasses. The layers of new lives were growing for the exchange. Was this a sublime of the decay, a picturesque of life? I took a picture of it.

Actually, the more experience in the landscape I took in, the fewer snapshots I took. I don’t like the picture frame that limits what I actually see: the human visual scope is being emphasized and reinforced. I don’t like that pictures tend to flatten actual spatial feelings: the single line on the picture representing the horizon far end of the world shortens and shrinks the actual distance. What’s the “picturesque?” How do I describe the depth of the ground, the distance of the space, the touchable closeness of the texture of the leaves, the birches next to me, the maple trunks far away?

Sun light came in. Shadows were everywhere including mine. The glade was still and so was I.

November 29. The third time in the woods.

One of the panels had fallen. It was rigidly frozen into the snow. I tried to pull it out, looking around for a new spot to re-install it. All the branches seemed fragile. Along with a crackling noise, a big pile of snow dropped, then the twig.

The woods looked prettier than ever. The solid gray stillness was frozen by the snow. The sound had been covered too. The thickness, heaviness, whiteness of the ground contrasted with the snarled, but lifeless stern trunks and branches. The wildness is tamed eventually.

I hung the frame on one spruce’s arm, which was big and maybe strong enough but too high. I climbed on whatever was under my foot to reach it. The dangling square adjusted itself for a while, then settled.

[1] https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/picturesque